When we first encountered young Karabo*, a 14-year old South African girl from Pholonhle in the North West Province, she was insecure, had low self-esteem and little hope for her future. She had experienced unspeakable tragedy having lost her mother just a few years earlier to AIDS and now felt like she was all alone in the world. She had never met her father and only knew that he was from Mozambique and had returned there before she was born.

The painfully shy teen found it difficult to connect with other people and had few friends. Karabo frequently skipped school because she said she felt inferior to the other kids. She was upset because she believed the other children treated her differently and pitied her because she was an orphan, and this only made her want to withdraw even further.

Karabo had lived with her 26-year-old aunt and a 24-year-old uncle since the death of her mother. The circumstances of her mother’s death never came up in conversations between the family members, as it is customary in that culture to shield children from disturbing topics. However, this silence contributed to Karabo’s feelings of disconnectedness.

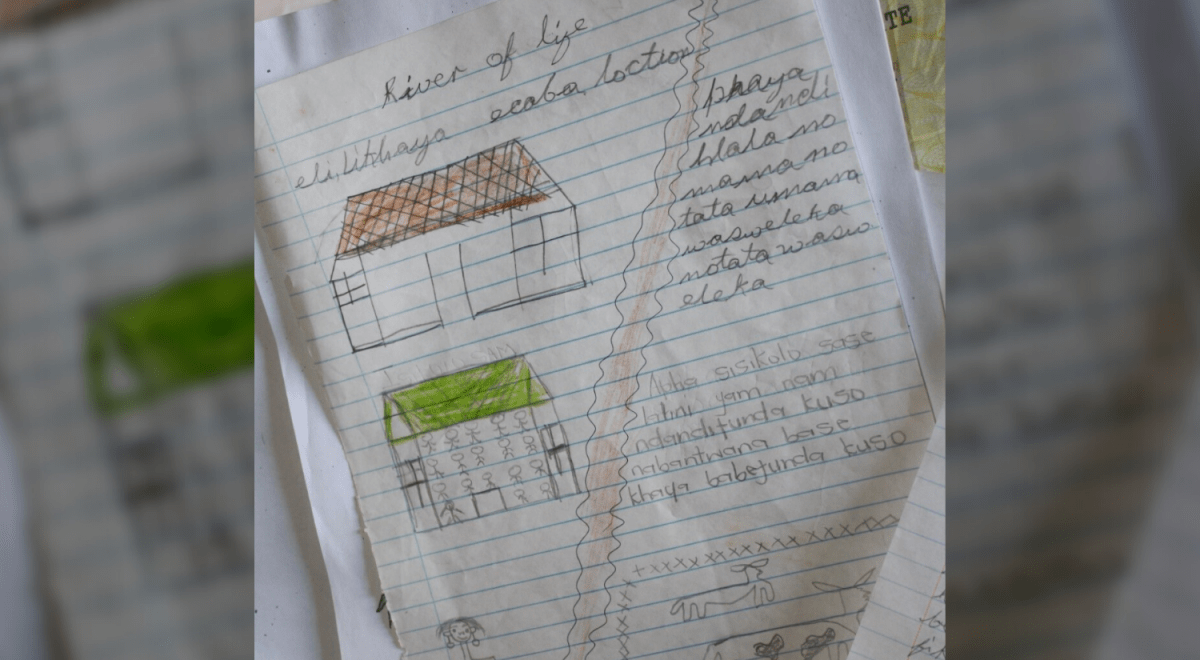

It wasn’t until Karabo met a therapist from Mpilonhle, a local organization working in partnership with CERI, that she began to have some hope of reconnecting with her roots. The therapist described a new program called Memory Box, a psycho-social intervention designed to help orphans regain silenced family memories. The program facilitates inter-generational dialogue and helps children and families regain their sense of self-worth.

The intervention was difficult for the whole family as Karabo’s aunt and uncle were still dealing with the loss of their sister as well. Karabo was saddened to learn about her mother’s illness and the troubles she had been through. But she also learned much about her family’s background, history and values. After therapy, Karabo’s relationship with her peers improved. She was better able to connect with them and make friends at school. She began attending school regularly again because she had found meaning, purpose and hope for her life.

Karabo now knew that she was a child like any other, with parents and a family, even though they were taken away by a terrible illness. She now had a better understanding of her place in the world and it gave her the confidence and stability she had been lacking. She could finally feel that she belonged.

Help more youth, like Karabo, find meaning and hope to thrive.